Basic commands

Software Engineering Team Lead and Director of Cloudsure

💡 Do you remember how to get to the help tutorial in the terminal?

git help tutorial

# or a specific command

git help git-<command>To get more documentation on a command, type

man git-<command>

# example

man git-logCommits

The goal of the game is to get changes into the popular VCS called Git. Ideally you want to get this onto a remote repository.

Changes are in the form of commits which contain a bunch of things that have changed and a message of the change. Let's break it down into smaller components.

Working directories status

Your working directory will show you what state it is in.

git status❯ git status

On branch main

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 3 commits.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: courses/git/02-about-git.md

modified: courses/git/03-terminology.md

modified: courses/git/04-installation.md

modified: courses/git/07-commands.md

modified: courses/git/index.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")We will cover the output of this command a little later. For now, all you need to know is that it shows you the files that have changed.

Diffs

It is important to know that Git will show you the differences made in a change set. You can see what lines, words or files have been added, modified or deleted.

<div

- className="bg-color-1 text-color-1-script m-0 px-0 py-1"

+ className="relative bg-color-1 text-color-1-script m-0 px-0 py-1"

>git diff <thing>

# use the filename of the file that you are working on

# use the commit SHA of a commit in the history

# use the term HEAD to view changes since the last commit

# use the branch name that you are interested in (more on branches later)

# use <commit1> <commit2> if you want a diff different commits

# use the above command in conjunction with a filename to see how that file has evolved over the two commits eg. <commit1> <commit2> untitled.html

# use <commit1>..<commit2> if you want to diff two commits relative to a common ancestor

# use origin/<branch>..<branch> if you want to see the differences in your local repository relative to origin (the remote repository)Stage changes

Git offers an intermediary between tracking files and the actual physical version history. That means that you can fine tune and craft a decent commit before committing to the history. It's like a quality gate to see exactly what changes you want to commit at that time. You can interrogate your diffs to make sure you are committing relevant changes and that sensitive or debugging changes are reverted or left out. This area is known as the staging area.

Once it goes into the Git history, it lives in Git forever!

git add <file> <file> <file>There is a

git add .command to tell Git to add every file but then you are bulk adding instead of crafting so don't do this. We will go into the finer details of some etiquette later on in the course.

❯ git add courses/git/01-vcs.md

❯ git status

On branch main

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 8 commits.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: courses/git/07-commands.md

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: courses/git/02-about-git.md

modified: courses/git/03-terminology.md

modified: courses/git/04-installation.md

modified: courses/git/index.mdIf you have files listed under changes not staged for commit then these files have been changed but have not been put

into the staging area with the git add command yet. You can simply discard those changes.

git restore <file>If you have files listed under changes to be committed it means that the files have been staged. The staging area lets you chop and change what you put into it so if you accidentally added a file you didn't want to then you can take the file out of the stage without losing your changes.

git restore --staged <file>If you want to see the diffs that are ready to be committed

git diff --cachedCommit to history

Git tracks content not files. When you commit a change then you are telling Git to remember what changed at that point in time. You are officially adding it to the Git history, or if you want to think of it differently, saving the change to Git.

You can consider commits to be checkpoints or snapshots of the current state of your content. There is no limit to the number of commits you can make or size of the commit that I know of.

Now that you have seen your changes in the form of diffs and got them ready to be committed by staging the changes, you can now commit to Git.

Commit message

You bundle a Git commit with a message that is visible in the history (or log). This let's you - and others - know what changed. If you do a good job at this then you can make everyone's lives easier when there are bugs or issues that pop up. Read about the guidelines in the Etiquette chapter of this course.

Official documentation

Though not required, it’s a good idea to begin the commit message with a single short (less than 50 character) line summarizing the change, followed by a blank line and then a more thorough description. The text up to the first blank line in a commit message is treated as the commit title, and that title is used throughout Git.

It's easy to craft a good commit message if you are committing changes properly by context rather than in bulk.

git commitA text editor will pop up asking for your commit message. Enter it using the guidelines above, save and quit.

If you want to commit with a message inline (makes it harder to add a body) then you can use the following command:

git commit -m "Something cool to write home about"Show commit

Each commit is given a number called a SHA. The SHA will identify that commit and you will be able to access more information for it.

git show <SHA>Send an email

git format-patch

# documentation

git help git-format-patchThis command turns a commit into an email and it uses the title on the subject line and the rest of the commit in the body.

👀 Etiquette

When you follow bad Git habits of creating silly, non-descriptive or invalid messages, you run the risk of confusing the hell out of other people and making it difficult to identify when a change was brought into the system and could be the potential root cause of it breaking which wastes valuable time as the developers need to dig into each commit to try figure out what happened.

😱 Vim

If you commit without the -m switch, your default text editor that could pop up could be Vim.

Just a heads up, if Vim does open, to save, press : to go into the command mode,

press w to write and then press q to quit.

If you don't want to save then it is :q! - note the exclamation mark.

Note that we covered a bit of Vim in the Terminal chapter of this course.

History

The project history of all your commits can be viewed in the log and we can go back and forth between commits to see the different revisions that exist.

git log

# Documentation

git help logIf you want to see complete diffs at each step:

git log -pIf you want the overview of a change in each step:

git log --stat --summaryThe below command shows a colorful condensed line consisting of a short SHA, subject line, how long ago the commit was authored relative to now and who authored the change.

git log --pretty='%C(yellow)%h%Creset | %C(yellow)%d%Creset %s %Cgreen(%cr)%Creset %C(cyan)[%an]%Creset' --graphAliases

The pretty git log command is a bit verbose and hectic to type each time.

A Git alias is a powerful option where you can create your own custom Git shortcuts.

You can configure the pretty print command as an alias as follows:

git config --global alias.lg log --pretty='%C(yellow)%h%Creset | %C(yellow)%d%Creset %s %Cgreen(%cr)%Creset %C(cyan)[%an]%Creset' --graph

# Access it by typing

git lgBranches

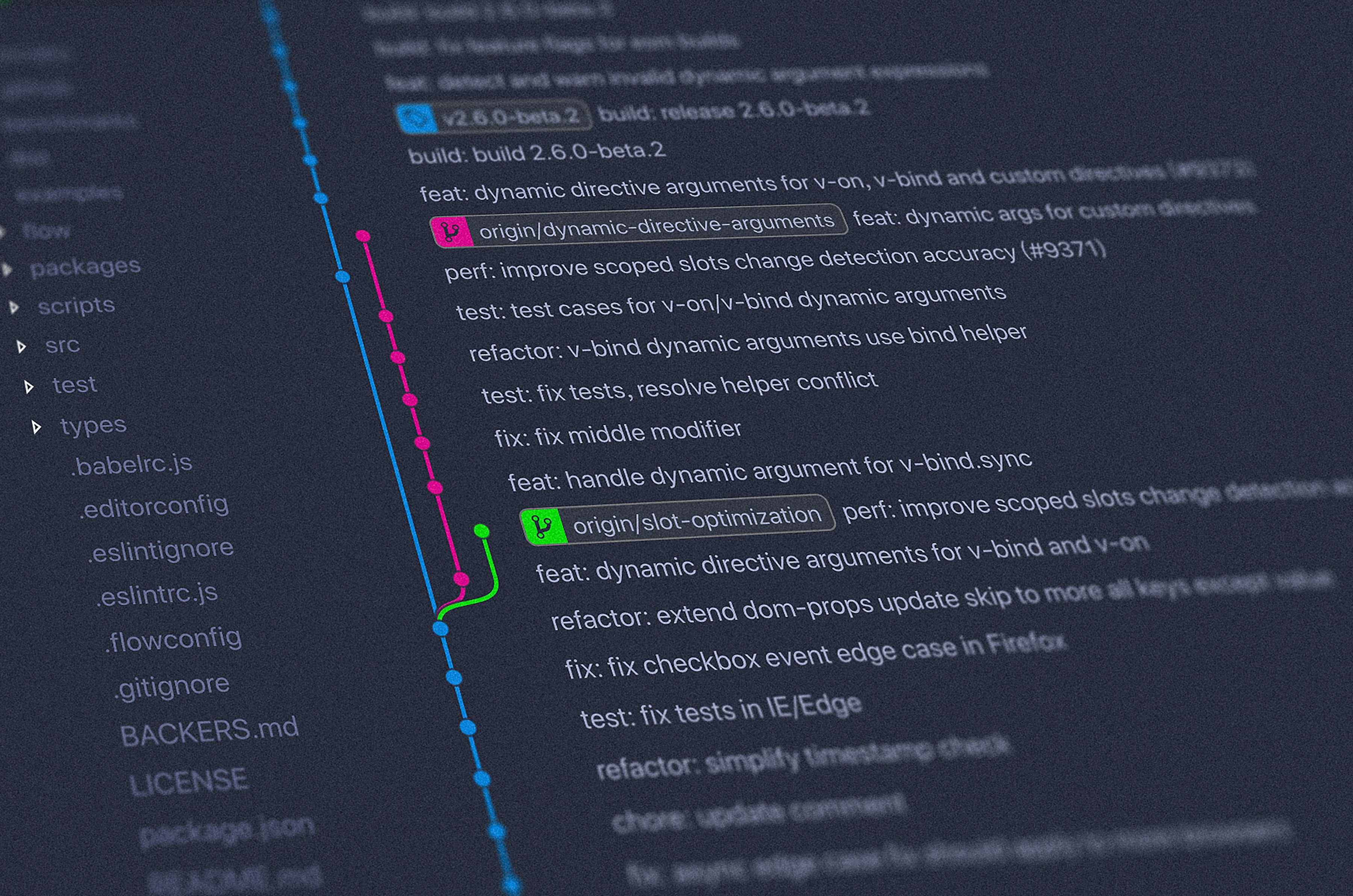

You can think of Git like a tree. Imagine your timeline of changes as you commit to your repository. This all happens on a branch. The main line of development is typically referred to as trunk (of the tree) or by its name of master or more recently main but it can be named anything.

You can deviate from the main line by creating your own branch where you can release a new feature, experiment, do work-in-progress or basically whatever you want, still push it to your remote repository without impacting others. A single Git repository can have many branches.

git branch <branch>In the image above, the blue line is trunk while the pink and green lines are separate branches that have been branched off of trunk at a specific point in time.

You can checkout a branch from a specific commit - so go back in time:

git checkout -b <branch> <SHA>See all your branches

git branch experimental

* mainThe asterisk marks the branch you are currently on so you will need to switch branches when you want to work on a different on:

Switching branches

git switch <branch>Let's have some fun shall we?

- Create a new branch off of your master/main branch

- Save a file with your favorite number it in

git commit -agit switch masterormaingit log

Do you see your change?

Merging branches

Your one branch has changes on it that the other branch does not have.

That means that the branches have diverged. If you want the changes on your branch to be put into the master/main branch

then you will need to merge those changes.

Be sure to be on the branch that you want the changes on.

git switch master

git merge experimentalIf you don't have any files that have content that conflicts then you are done. 😁 If there are conflicts 😱 then you will need to deal with obnoxious, loud (but helpful) markers that are left in the problematic files that show the conflicts.

Note that you should not change the merge commit message as one is automatically created for you.

Merge conflicts

You will need to fix files by resolving the conflicts (which we cover in a later chapter).

git diff

# Fix each file

git commit <file>Delete branches

If you want to delete a branch when you are done with it then switch it with -d. If the branch has not been merged

you will need to use -D.

git branch -d experimentalBranches are cheap and easy so this is a good way to experiment.

Git syncing

Remote repositories

You would have had to set up a remote repository to connect to. This is a repository - often hosted in the cloud - most likely on GitLab, GitHub, BitBucket or some other cool or custom place repositories can be hosted.

Some services offer public or private hosting of repositories. A public repository is available to anyone and is often Open Source whereas private repositories often have sensitive domain logic or information that developers or companies don't want to make public.

Remote repositories are useful because they foster collaboration and provide help during disaster recovery (imagine your machine goes 💥).

Your default remote repository will most likely be called origin.

git remote show origingit remote add <name> <url>

# name = default is usually origin

# made a spelling mistake?

git remote rename <old-name> <new-name>Clone

As Git is distributed, we do a Dolly the sheep, and make a clone of the repository on your local machine so that you can work on it. The clone of the project is an exact copy of the original project on the remote server.

git clone <url>There are two ways to clone: using SSH and using HTTPS. It is highly advised that you use SSH which you will learn in the SSH chapter of this course.

Push

You are probably going to be doing some work on the repository you just cloned. Once you have made a bunch of changes, you quadruple-triple check your diffs before you commit your changes. Once you have quality commits, you are ready to get your changes onto the remote repository. To do this, you will push to the appropriate remote.

git push <remote> <branch>

# Example

git push origin mainPull

Now that people are hacking away at the files on the repository, you will need to get copies of their files. Now you will pull changes from the appropriate remote.

Two operations are performed:

- The changes are fetched from the remote branch

- The changes are merged into the current branch using the strategy you configured

Stashing changes

If you have local changes you won't be able to pull. You will either need to commit, discard or put your changes away for later in the form of a stash.

git stash -m "Git course materials"You can apply the stash once the changes have been merged by listing all changes in the stash, getting the stash number and then popping that number from the stash.

git stash list❯ git stash list

stash@{0}: On main: Git course materialsgit pop stash@{0}You may encounter merge conflicts which you will need to resolve like you did before.

Fetch

A fetch will get stuff from the remote repository so that you can see what other people have done - you can peek at their changes.

It is important to note that the files in your local repository are not affected. You need to explicitly checkout that work. That means that fetching is a safe way to review commits before integrating them with your local repository.

git fetchTagging

git help git-tagOnce purpose of a tag is to annotate a particular commit for a particular release.

git tag v1.0.42 HEAD

git push --tagsBlame

If you need to see who made what changes to a particular file you can blame the file.

git blame <file>Searching

You can search for strings in any version of your project using the git grep command.

git grep "something"Status

Let's go back to git status. In the output below, there are no changes that have been detected. This means that the working directory (tree) is clean and that there is nothing to commit.

❯ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

nothing to commit, working tree cleanYou would see something similar to the output below if there are changes detected.

❯ git status

On branch main

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 8 commits.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: courses/git/01-vcs.md

modified: courses/git/02-about-git.md

modified: courses/git/03-terminology.md

modified: courses/git/04-installation.md

deleted: courses/git/index.md

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

git-status.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Interesting! Note the following information I can see from this output:

- I can see the branch that I am working on: main.

- My local branch has 8 commits more than the remote repository origin/main.

- I have changes that have not been staged for commit (5 files)

- I have 1 change that is untracked.

Advanced commands

Many Git commands take sets of commits:

git log v2.5..v2.6 # commits between v2.5 and v2.6

git log v2.5.. # commits since v2.5

git log --since="2 weeks ago" # commits from the last 2 weeks

git log v2.5.. Makefile # commits since v2.5 which modify MakefileYou can also give the log a "range" of commits

git log -p origin/main..main # commits between origin/main and local main branchThe following are a few advanced concepts that will be covered in another course.

- Rebase

- Drop

- Reorder / Reword commits

- Reset commits

- Squash

- Cherry pick

- Stage hunks

- Bisect

Get a sneak peak of some commands.

Recap

In this video, Colt Steele gives a quick run down of Git in 15 minutes. Learn about adding, committing, branching, checking out and merging. He has made notes available to follow with.

In this video, by LearnWebCode, you'll go over some vocabulary used in Git and to see Git in action.

In this hour long video tutorial, Programming with Mosh, will teach you the fundamental concepts and some important Git commands. At the end of this video you will have a good understanding of the basics and be ready for intermediate to advanced concepts.

Bonus! 😍 Get the Mosh Hamedani's cheat sheet - author of the video below.

Chapter objectives

✅ You should be able to recognize and use basic Git commands outlined in this chapter.

✅ You should know how to get help directly from the command line using the man pages or git help git-<command>.

✅ You should have a basic understanding of how to craft a good commit.

✅ You should be able to read a diff.

✅ You should be able to navigate the history (log).

✅ You should understand branching, how to switch between different branches, how to merge changes onto the different branches and how to delete them.

✅ You should be exposed to Merge Conflicts and have an idea of how to resolve them.

✅ You should be able to work with remote repositories and know how to clone, pull, fetch and push changes.

References

- What is Gitignore and How to Add it to Your Repo - freecodecamp.com

- Gitignore templates - GitHub

- Git Diff - Initial Commit

- Git Config - Atlassian

- Git Cloning - Atlassian

- Git Syncing - Atlassian

- Git Workflow - Atlassian

- Git Branching - Basic Branching and Merging - Official documentation

- Git Tools - Advanced Merging - Official documentation

- Vim - Quick Guide - Tutorials Point

- Ubuntu on WSL